A skeptical allegation these days is that the Gospels were not written by the traditionally-recognized authors. One reason for this conclusion is essentially that there are no titles or authors’ names mentioned in the text of each of the gospel accounts traditionally ascribed to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

According to the prolific New Testament scholar Bart Ehrman, “[S]ome books, such as the Gospels… had been written anonymously, only later to be ascribed to certain authors who probably did not write them (apostles and friends of the apostles).”1

The titles we do read at the beginning of the four Gospels were added only later, he claims, and were only the opinions of the scribes who added them.

Technically, Ehrman is right — the four Gospels are “anonymous”, in that the author’s name is not explicitly listed in the text, but that does not mean that they were initially presented as texts without authors! It does not mean that we can’t be confident who wrote them.

In ancient times the omission of an author’s name in a text was not an unusual practice. We have literature written by Plato, Plutarch, Lucian, and Porphyry that do not contain their name in the text itself and are every bit as ‘anonymous’ as the Gospels, in that sense. But this by no means suggests that we have no idea who the authors were.

The respected New Testament scholar Martin Hengel, pointed out that it is “… unlikely and unrealistic to think that such [early Christian] writings could have left their original communities without titles since such works needed both a generic identification as well as some personal authorization.”2

After all, what is the first thing a person would ask when presented with a brand-new writing? “What’s it about and who wrote it?”

Does it really make sense that the scrolls would have arrived without the identity of the author being known and communicated to those receiving it?

Additionally, people distrusted anonymous works without any identification of some kind. Forgeries existed in the ancient world, including among Christians, but they were rejected as deceptive when discovered.

Forgeries existed in the ancient world, but they were rejected as deceptive when discovered.

Even Ehrman, who is known for his skepticism agrees, “Ancient sources took forgery seriously. They almost universally condemn it, often in strong terms.”3

Among early Christians this was especially the case. They held to the clear teachings in the Hebrew Scriptures that God does not lie and he hates deception. Lying was never tolerated (see Proverbs 12:22; Leviticus 19:11).

New Testament specialist Eckhard Schnabel explicitly states, “The early church rejected writings … [whose] authorship was pseudonymous” (that is, had a false name attached to it).4

Because anonymous texts were distrusted, texts were never really completely anonymous! The recipients of a new text would make sure they knew who the author of the text was before they would use it.

So the argument goes like this:

- If the Gospel's author was not known, then it would not have been trusted by the early Christians (because anonymous texts were distrusted).

- The Gospels were trusted by the early Christians.

- Therefore, the Gospels’ authors were known.5

They must have been identified in some way, even if the author’s name was not in the text itself! Otherwise the earliest Christians would not have trusted them as they did.

The oldest extant Gospel manuscripts that include the very beginning of each Gospel are from around AD 200. Without exception they all include titles written before the beginning of each text in the form ‘The Gospel According to...’

Notre Dame New Testament scholar Brant “Pitre points out the obvious (but for Ehrman, very problematic) fact that ‘there is a striking absence of any anonymous Gospel manuscripts. That is because they don’t exist. Not even one.’”6

On the contrary, all of our earliest gospel manuscripts contain the titles that attribute these books to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

Sure, it is logically possible that scribes added these titles to the beginning of each Gospel’s text at some relatively later point prior to (AD 200), attributing them to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. But possibilities come cheap! It is also logically possible that knowledge of the authors accompanied the gospel writings from day one!

Numerous scholars think that

- the very existence of the titles,

- their unusual form,

- and their universal use actually strengthen our confidence in traditional authorship rather than undermine it.

Hengel argued convincingly that the meaning of this title form ‘The Gospel According to ...’ is actually The Gospel (the one and only gospel message) according to Mark’s account (for example). That is, there is only one Gospel message, but there exists more than one author’s account — hence the term “according to”. This is affirmed by other broadly respected New Testament scholars, Glenn Stanton and Richard Bauckham.7

Thus, the very existence of titles, especially in this form, presupposes the existence of other Gospel writings because it became necessary to distinguish between more than one early Gospel accounts. Bauckham argues, “A Christian community that knew only one Gospel writing would not have needed to entitle it in this way.”8

The universal use of titles in this form, as soon as we have any manuscript evidence, shows that the titles originated very early in Church history.

Bauckham adds “Whether or not any of these titles originate from the authors themselves, [which I would add is feasible] the need for titles that distinguished one Gospel from another would arise as soon as any Christian community had copies of more than one in its library and was reading more than one in its worship meetings… it would have been necessary to identify books externally, when, for example, they were placed side-by-side on a shelf.”9

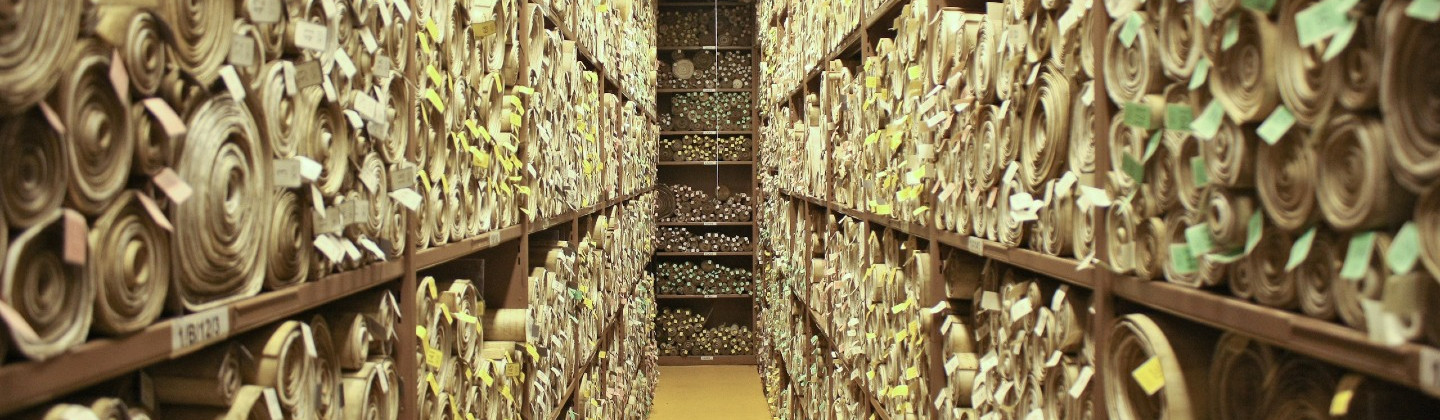

Obviously, since scrolls are rolled up with the texts on the inside — some external identification would be necessary, and this is exactly how we see scrolls stored from antiquity to this day.

Bauckham adds, “For this purpose [of identification] the short title with the author’s name will be written either on the outside of the scroll or on a papyrus or parchment tag that hung down when the scroll was placed horizontally on a shelf.”10

So titles may not have been included in the text initially but rather identified on the outside of the scroll in some way.

This implies that, as Bauckham puts it, “Gospels would not have been anonymous when they first circulated around the churches. A church receiving its first copy of one such [Gospel] would have received with it information, at least in oral form, about it's authorship and then used its author’s name when labeling the book and when reading from it in worship.”11

According to Hengel, these traditional titles that are found in the very early manuscripts (AD 200 on) are very likely the same titles that were first attached to the original scrolls from the beginning or no later than when the churches had to label the scrolls for use and for circulation.

If this were not the case - if titles were added much later because no one knew who wrote them, then how do you achieve such uniformity in this unusual title form?!

Bauckham emphasizes, “Once the Gospels were widely known it would’ve been much more difficult for a standard form of title for all four Gospels to have come into universal use.”12 The manuscripts would more than likely have a variety of title forms – not all have exactly the same form ‘The Gospel According to...’

Moreover, if the Gospels had circulated anonymously for more than a century (as Ehrman argues), then we would expect them to have a variety of different titles, as well as forms of titles. Surely, we couldn’t expect them to circulate anonymously for more than 100 years, and then suddenly all early Christians separated by thousands of miles within the Roman Empire without Mail service, UPS, or the internet, use precisely the same form and titles.

If titles were added much later, how do you explain their uniformity?

A work circulating without a title would have picked up a multiplicity of titles, which did not happen with the New Testament gospels. There is no evidence that these Gospels were ever known by any other names.

Pitre responds to Erhman’s suggestion the titles were added much later: “This scenario is completely incredible. Even if one anonymous Gospel could have been written and circulated and then somehow miraculously attributed to the same person by Christians living in Rome, Africa, Italy, and Syria, am I really supposed to believe that the same thing happened not once, not twice, but with four different books, over and over again, throughout the world?”13

Not very likely!

Summary of the argument and implications

The attempt to draw the conclusion that the gospels were originally anonymous because the original texts did not contain titles or author’s names does not seem to be the most reasonable conclusion for the following 5 reasons.

- In ancient times the omission of an author’s name in a text was not an unusual practice.

- The first thing a person would ask when presented with a brand-new writing is “what’s it about and who wrote it”?

- Ancient Near Eastern people, especially Christians, distrusted anonymous and pseudonymous writings, but did not distrust the gospels. Therefore, they must have known who the authors were.

- All the earliest gospel manuscripts (that contain the beginning) contain the titles in the form ‘The Gospel According to ...’ — where the author’s name fills in the blank. This would have been unnecessary if there had only been one written gospel account. Therefore, there was more than one written gospel account very early in church history. It is likely, then, that the authors’ names were on the outside of the scrolls to distinguish the different accounts from each other. The accounts must not have been anonymous when first received.

- If there were no authors’ names placed on the outside extremely early, how did the title format achieve such uniformity in its unusual design and across such distances? If the gospels had circulated for more than 100 years, then we would expect them to have a variety of different title forms and authors. Once the gospels were widely known and dispersed, it would have been much more difficult (virtually impossible) for a standardized form of title for all four gospels to have come into universal use. The manuscripts would more than likely have had a variety of title forms, as well as authors.

It is not absolutely essential for the reliability of the gospel accounts that they are proved to be written by Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, although it does add support to the claim that the gospels are based on eyewitness testimony. But it does not follow assuredly from the fact that there are no titles or authors names mentioned in the text of each of the gospel accounts, that the gospels were not written by the traditional authors. This skeptical allegation fails.

References

- Bart Ehrman, Jesus Interrupted (2011), pp. 101-02

- “The Genre of the Didache: A Text-Linguistic Analysis, Dissertation”, Nancy Pardee, University of Chicago, 2002, 113, (Cited in Ron Jones, The Manuscript Evidence of the NT Gospels: Affirmation for the Authorship of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, http://jesusevidences.com/manuscriptevidence.php

- Bart Ehrman, Jesus Interrupted (2011), pp. 115

- Cited in Jonathan Morrow, Questioning the Bible: 11 Major Challenges to the Bible’s Authority, 2014, p. 89

- This conclusion follows logically according to the rule of inference called modus tollens which takes the form of “If P, then Q. Not Q. Therefore, not P.

- Cited in Michael Kruger, Two Very Different Books on the Reliability of the Gospels, a review of Brant Pitre’s The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ. (Image, 2016) https://www.michaeljkruger.com/two-very-different-books-on-the-reliability-of-the-gospels/

- Cited in Richard Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, Eerdmans, 2006, p. 302

- Ibid

- Bauckham, p. 303

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Cited in Michael Kruger, Two Very Different Books on the Reliability of the Gospels, a review of Brant Pitre’s The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ. (Image, 2016) https://www.michaeljkruger.com/two-very-different-books-on-the-reliability-of-the-gospels/